De Vries et al., (1997) observed in five out of 35 patients a halting in tumorgrowth during three to nine months, and in one case even two years, following individual and group psychotherapy.

Therapy was existential and experiential, was influenced by findings in patients with spontaneous remission of cancer, and was directed at increasing autonomy, social support and meaning in life.

Goodwin et al. (2001) and Kissane et al. (2007) good not replicate these findings. Their therapists had only a two day training by Spiegel and they used the therapy manual. Maybe this accounts for the difference. Spiegel and collegues had stressed the necessity of therapists joining the groups for several months before leading them, long before they reported the longer survival.

Kuchler et al. (1999) (2007) worked differently: they gave individual psychotherapeutic counseling to patients with gastro-intestinal cancers in the days before and after their surgery. Anxiety and depression were explored, as well as coping with the diagnosis. With their personal therapist, patients looked how they had coped earlier in their life with threatening situations. The therapists provided ongoing emotional and cognitive support to foster “fighting spirit” and to diminish hope- and helplessness. Also, patient and therapist investigated how the patient could increase social support ( for an inspiring example of creating social support, see the end section of this account). Emphasis was placed on assisting the patient in forming questions for the other caregivers. While maintaining appropriate confidentiality, the patient’s overall well-being was routinely discussed with the surgical team. More than 95% of inpatient interventions took place on the ward, and the remainder at other places within the hospital. Before discharge, the therapist explored the patient’s emotional and cognitive interpretation of the surgery, and assisted the patient in planning for the future.

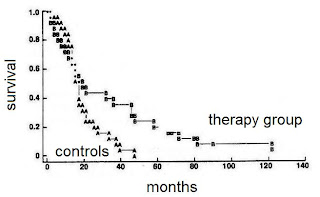

Longer survival was seen amongst the patients that received this bed-side psychotherapeutic support.

Kuchler et al. 2007; longer survival in gastro-intestinal cancer after psychotherapeutic support J. Clin. Oncol. 2007.

It is of great interest that the gain in survival holds on for so long. And for a relatively cheap intervention of less than an average of four hours of patient-therapist contact. As Andrykowski stated in the editorial of the Journal of Clinical Oncology: "I know of no medical intervention that could be implemented with gastrointestinal cancer patients that would be expected to deliver this big a bang for so few bucks."

Overall, experiential, existential, supportive therapies, directed at autonomy, feeling and expressing, supportive relationships, meaning and active coping seem promising, notably when they are performed by therapists who are experienced in working with cancerpatients. Interestingly, cognitive behavioral intervention (CBT), directed at 'restructuring maladaptive thought', sofar has not shown effects on survival. Edelman et al. (1999), give an interesting example of one of their interventions. This may shed some light on our theme. A woman with breast cancer came home after hospital visit. The husband had not accompanied her, nor was he waiting for her when she came home. He showed no interest in what had happened. In the therapy-group the patient expressed her distress; she felt that he did not love her. In experiential therapy, the therapist likely would have explored this feeling. Maybe it is for the first time in her marriage -or life- that the patient is daring to experience the painful possibility that she is not loved. Awareness of this possibility, if it is correct, at least may bring congruence between emotions, cognitions and behaviour, thus lowering repression. Possibly, it might bring some improvement of the relation as well. Yet, in the cognitive therapy, the therapist tried to 'correct the maladaptive thought' of the patient, trying to convince her that this behaviour of the husband not necessarily implied that he did not love her. In the early nineties, Wilhelmsen et al. (1990; one of the 'alieni' being Holger Ursin) reported that they had had to interrupt their study with cognitive psychotherapy for patients with duodenal ulcers because of increased relapse in the treatment group. This was just before the era of protonpump inhibitors. Although not about cancer, this study points to a physically harmful effect of CBT.

Increased relapse of duodenal ulcers in patients treated with cognitive psychotherapy (Wilhelmsen et al., The Lancet, 1990)

'Maladaptive thoughts' usually originate from deeper emotional pain and hidden wounds. Cognitive change will never cure that. It is just another form of unhealthy 'emotion focused coping'. But this does not imply that cognitions are useless. Fawzy et al. gave a course, aimed at improving active coping, to patients with melanoma. This intervention only consisted of six weekly meetings of 1,5 hour each. Yet, a substantial effect on survival was seen.

In their later analysis (2003) it turned out that the effect on survival of this short intervention also lasted up to ten years.

Looking at their data in more detail, Fawzy et al observed that the effect on survival was most clear in patients that had developed active coping. Thus they stated: "If coping improves, so does survival". Psychodynamic, experiential approaches and a course in problem focused coping may seem an illogical combination. They may, however, form a paradoxical synergy. See for some further remarks: Psychodrama and Cancer.