Forsen and Luoma (1992) observed that women with breast cancer who considered themselves 'original, independant, special' had longer survival than women who said that they were 'usual, as the others'.

(© Forsen and Luoma, 1992)

Similarly: women with breast cancer who thought of themselves as willing to engage in conflict and, if necessary, being 'quite hard', survived longer than those who said they were 'very sensitive' and tried to avoid conflict.

(© Forsen and Luoma. 1992)

Possibly, the content of these questions has helped to get the right answer: we can imagine that women who view themselves as original and independant, likely dare to present themselves as such. On the contrary, women who view themselves as 'usual, as the others', likely will state that they are like this. Therefore the nature of these questions may have helped to surpass disturbing effects of social desirability, façade and repression. This may have contributed to these fascinating differences in nature, and their effects on survival, becoming clear.

Viewing oneself as original, independant and special may reflect an inner state with more 'degrees of freedom', possibly due to more access to different aspects of oneself (see psychodynamics in oncology), including more hostile aspects if necessary. Stavraky saw a similar relation already in1968, when he observed longer survival in patients with various types of cancer, characterised by high hostiliy without loss of control. In line with this, Derogatis (1979) saw shorter survival in women with breast cancer with low hostility. Related to this is the observation by Renneker, a psychotherapist who worked with cancer patients: "The first aim of a cancer patient is to please someone else; the second aim is not to displease someone else".

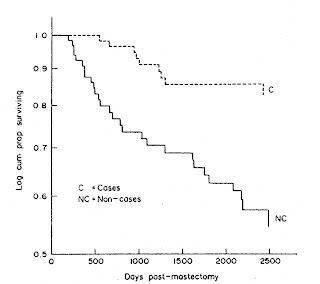

Another concept that got much attention is fighting spirit: an active attitude, directed at 'fighting the disease', from a hopeful and optimistic point of view. Initially, Greer et al. (1979) and Pettingale et. al (1985) had seen longer survival in women with breast cancer and high fighting spirit.

(Pettingale et al., 1985, © The Lancet)

However, Dean and Surtees (1989) could not replicate this finding regarding fighting spirit. Interestingly: they did confirm the protective effect of denial; from a psychotherapeutic point of view possibly a counter-intuitive finding, yet valuable and intriguing. The negative finding with regard to fighting spirit is one of those examples in psycho-oncology, where negative and positive observations led to further questions and insight. Greer postulated that apart from true fighting spirit, patients could also exhibit 'pseudo' fighting spirit: patients who say they will do everything to survive, but who do so, not from an inner autonomy, will and 'positive outcome expectancy state' (Ursin's nice definition of good coping), but rather because of some feeling that one is supposed to do whatever one can, either from a moral stance, for oneself, or to please familiy, friends or even medical doctors; maybe even because of hopeleness:

(Dean en Surtees, (1989); © Journal of Psychosomatic research).

With regard to fighting spirit, Tschuschke et al. (2001) assessed fighting spirit by means of interviews and more extensive quantitative and qualitative analysis. Fighting spirit was considered present, when they observed the intention to conquer the disease and not let fate ruling life, and when there was optimism, hope, taking initiative and encouraging oneself by looking back at earlier crises in life that were overcome. Assessed this way, fighting spirit again was related to longer survival.

(Tschuschke et al., (2001), © Journal of Psychosomatic

Research)

Several workers have shown increased survival in more 'psychologically' symptomatc patients; Rogentine et al. (1979) in melanoma, Derogatis in the same year in breast cancer patients.Differences may be large: More psychological symptomatic melanoma patients showed 80 % one year survival, versus 30% in patients who outwardly seemed 'well adjusted'.

So, what you see on the outside, is not what you get. Schoen (1993) asked a group of seriously ill patients, including cancerpatients, if they were willing to get better. Nearly all did. Then he applied mild hypnosis and asked again, while patients used their hands to answer. Nearly 40 % of the patients now indicated that they did not want to get better at all. At this, more unconscious level, they either perceived the disease a a justified punishment for things that had gone wrong in their life, or as a way out of problematic life-situations that were perceived as insolvable.